Pitfalls of the American Community Survey

Data methodology is like the nutritional information on a box of cereal. Everybody should take time to read and understand it, but most of the time we just look at the picture on the front of the box.

As local governments and organizations begin to rely more on data to drive their decisions and justify their policies, the general public needs to be better consumers of data along with them. The American Community Survey is one of the most powerful and frequently used compilations of data open to the public. Local governments and organizations should understand its limitations before using it as a shortcut for local data.

The U.S. Census Bureau supplements the decennial census with the ACS as a way to publish data about the American population at a higher frequency. But the shift from the census’ large-sample, low-frequency methods to ACS’s small-sample, high-frequency methods come with a trade-off.

The Census Bureau gains a higher frequency of data, but loses the resolution of the data by switching from the long-form decennial census to the ACS. The Census Bureau estimated that the amount of uncertainty (margin of error) in ACS data is 33 percent higher than the census. But current ACS data is estimated to have margins of error 75 percent higher than the census. To address this, the Census Bureau publishes the margin of error for each ACS dataset so that its users can be aware of the degree of uncertainty. In addition, they increased the sample size from 2.9 million individuals to 3.5 million.

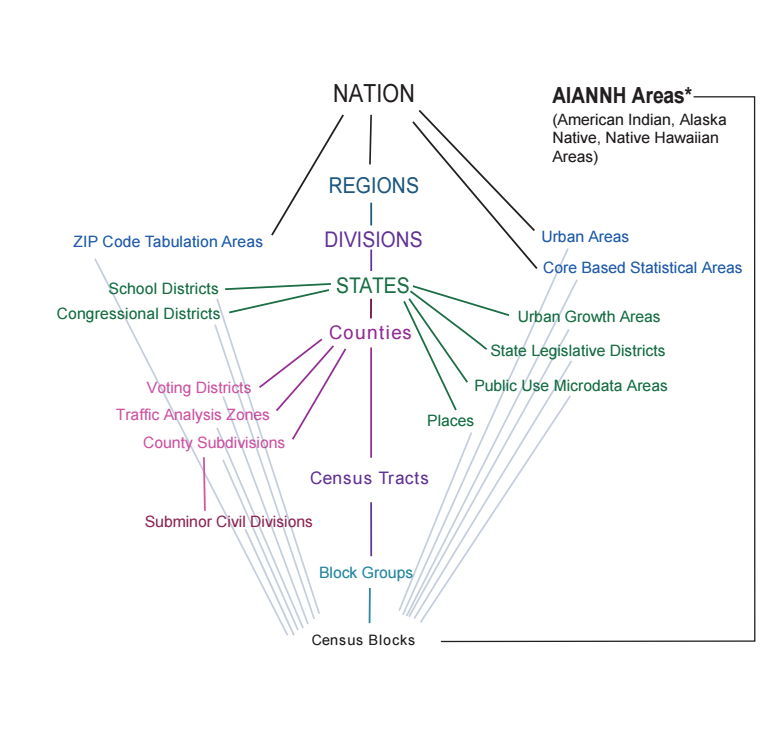

Despite efforts to mitigate uncertainty in ACS data with larger sample sizes, the reliability of its data can still be poor for small areas. The Census Bureau reports summary data on various geographic levels from their smallest unit – the census block – to the national level.

The margins of error in ACS data grows as the size of the geography decreases. To counteract this effect, the Census Bureau pools multiple year samples into three-year and five-year estimates. But even the five-year estimates at the census tract level contain levels of uncertainty that can make some of the data unreliable.

Local governments and organizations trying to find socioeconomic data for areas in their counties or cities would have difficulty getting consistent data from the ACS. Its data is compiled primarily from county-level statistical samples — making disaggregating the data to the tract, block group and block levels challenging. Not all ACS tract level data is unreliable. Some, of the data is extremely valuable. But, local governments and organizations need to be cautious in how they use it in their work.

The Census Bureau measures the reliability of data based on an estimate’s coefficient of variation (CV). The CV is a standard measure of the amount of sampling error in the estimate relative to the size of the estimate itself. The Census Bureau’s established thresholds of reliability are:

| Level of reliability | CV range | Type of estimates |

|---|---|---|

| High | < 12% | Reasonably reliable |

| Medium | 12–40% | Used with caution |

| Low | > 40% | Very unreliable |

These are only generalized thresholds, and the amount of acceptable error is subject to the analysis being conducted.

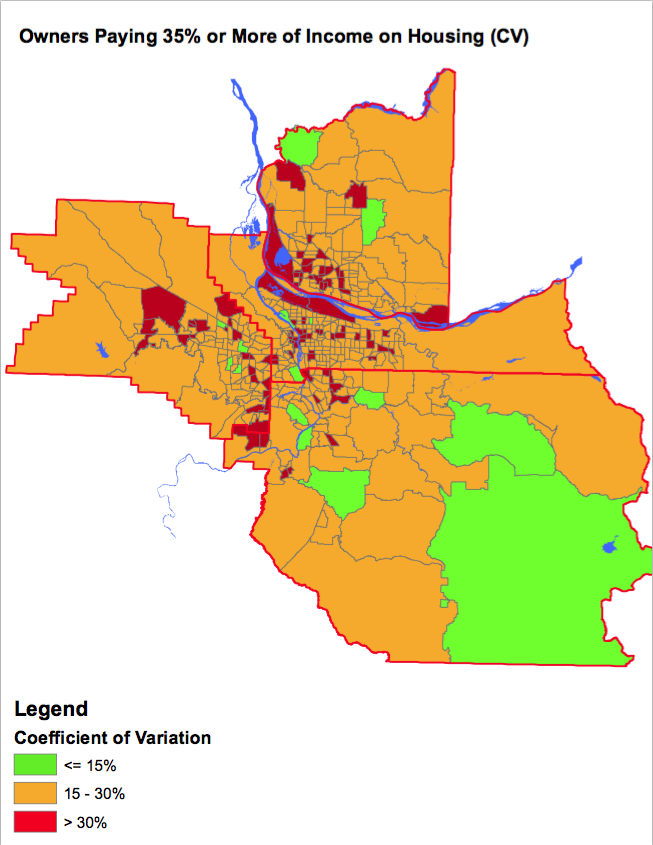

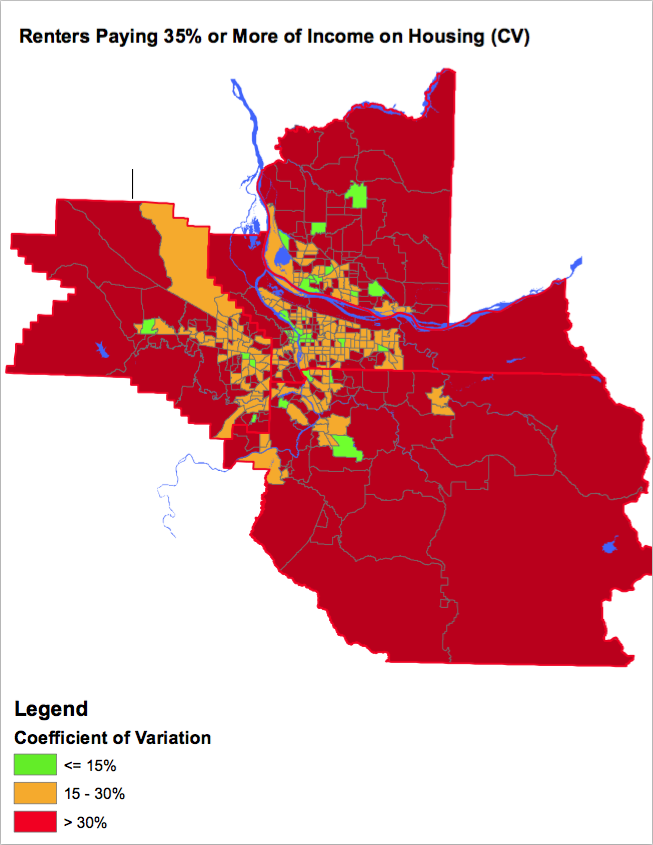

The Regional Equity Atlas mapped out the CVs on the 2011 ACS five-year estimates for the tracts in a county.

The maps show the volatility of the data’s reliability across census tracts. Although the data is not from the most recent five-year estimates, it’s consistent with ACS’s current methods.

The ACS is an incredible resource for data at higher levels of geography. But it sacrifices geographic resolution for higher frequency. This puts a limit on how local organizations can use it to look at socioeconomic characteristics within their areas. For local governments and organizations, this makes the supply of government open data incredibly important. Local governments should not only be making their data open to the public, they should be investing in their own data collection capabilities.

Using data to inform decisions on policies and the allocation of resources should not be optional for local officials. It should be the standard for local governments to generate, and use, local data to provide data-driven solutions for their communities.

Abby Attia

Abby Attia moved to East Tennessee from Amman, Jordan. She is studying political science at Lee University. As a student, she has interned for the city of Chattanooga, Heritage Foundation and Metro Ideas Project.